In straightforward terms, the Sunny 16 Rule is a rule of thumb that can determine the correct exposure time for an image outdoors under bright sunny conditions. The number 16 refers to the aperture setting on a camera lens.

This rule states that for daylight photography, you should set your camera’s aperture to f/16 and adjust your shutter speed until the meter says it is the inverse of the ISO number.

What Is the Sunny 16 Rule in Photography?

The Sunny 16 Rule states that a good exposure should be obtained when the shutter speed is same as the ISO and the aperture is set to f/16.

There is a misconception that the ISO always has to be set to 100. It’s not correct.

As long as the shutter speed is the inverse of the ISO number, you can use any ISO you may choose.

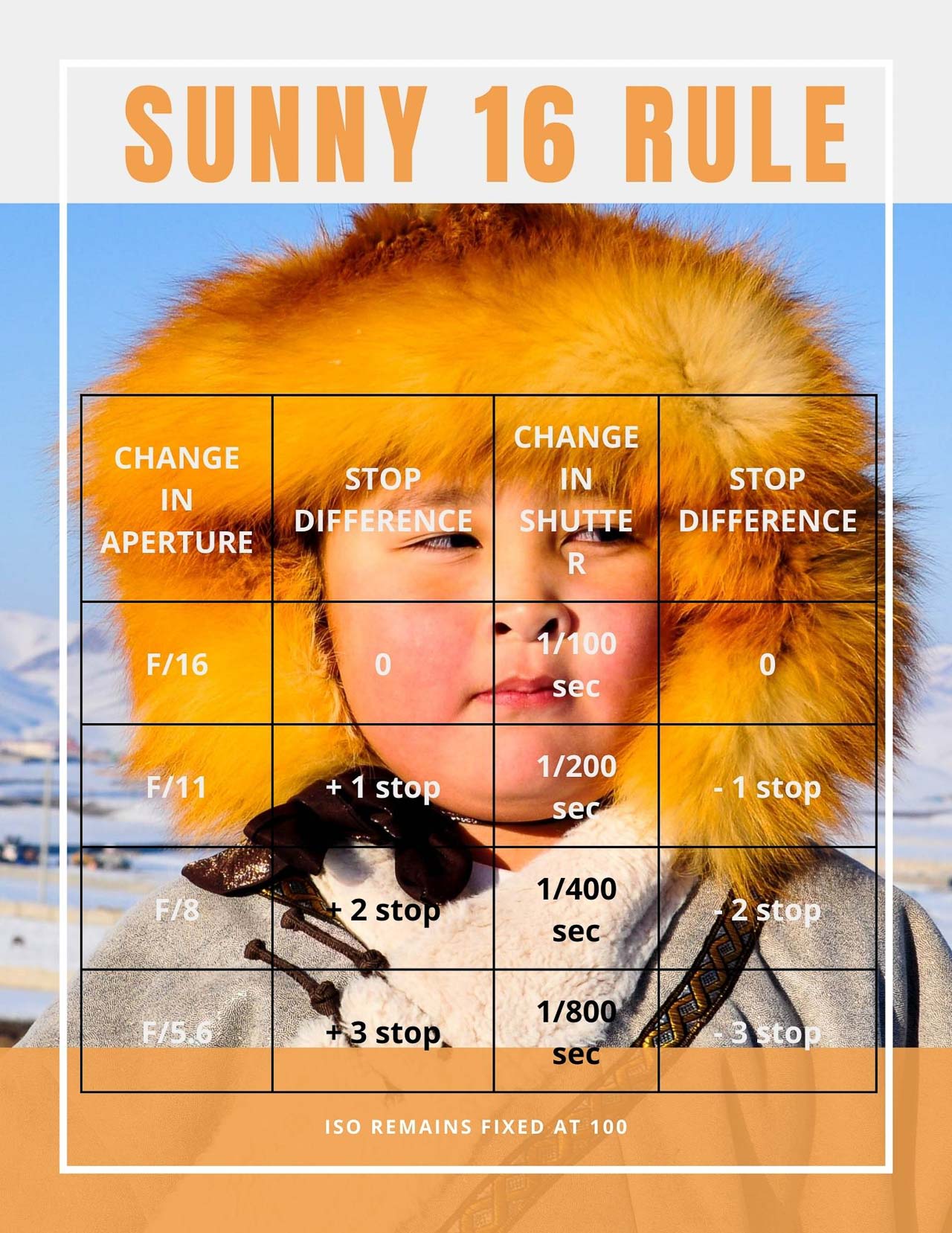

The Sunny 16 rule can be better explained using a chart. As they say, a picture speaks a thousand words!

As you can see above, the base value on which everything is based is aperture f/16. That’s the starting aperture you should use on a bright sunny day. It’s also assumed that the ISO is set to the lowest on your camera. Most cameras have a minimum ISO of 100. So, set your camera to ISO 100. Some older cameras can only drop till ISO 200. Don’t bother; set your camera to ISO 200.

As per the Sunny 16 rule, the shutter speed should be the inverse of the ISO value.

That means if you have set your camera to ISO 100 shutter speed should be 1/100 sec. And if you have set it to ISO 200, the shutter speed should be 1/200 sec.

What if You Want to Change the Depth of Field?

The first question that comes to everyone’s mind is the Sunny 16 Rule seems to limit the camera settings to f/16, ISO 100, and shutter speed 1/100 sec.

But what if a photographer needs to play with the depth of field?

F/16 isn’t always the preferred or the most feasible way to shoot, not even when it’s brightly lit outside.

Let’s say that you want to move to f/5.6, three stops faster from f/16.

We have already seen that the Aperture and Shutter Speed of a camera has an inverse relationship with each other.

Opening the aperture to f/5.6 to create a shallow depth of field also invariably lets in more light (thanks to the larger aperture). So, you have to speed up the shutter speed to ensure that the exposure is correct.

Look at the chart; this should give you a fair idea of the revised shutter speed. Every time you increase the aperture of your lens by one stop, the shutter speed should speed up by precisely one stop to compensate.

The beauty of the Sunny 16 rule is that it gives you a reasonably accurate starting point, and you can base all your subsequent exposures values using that as the starting point.

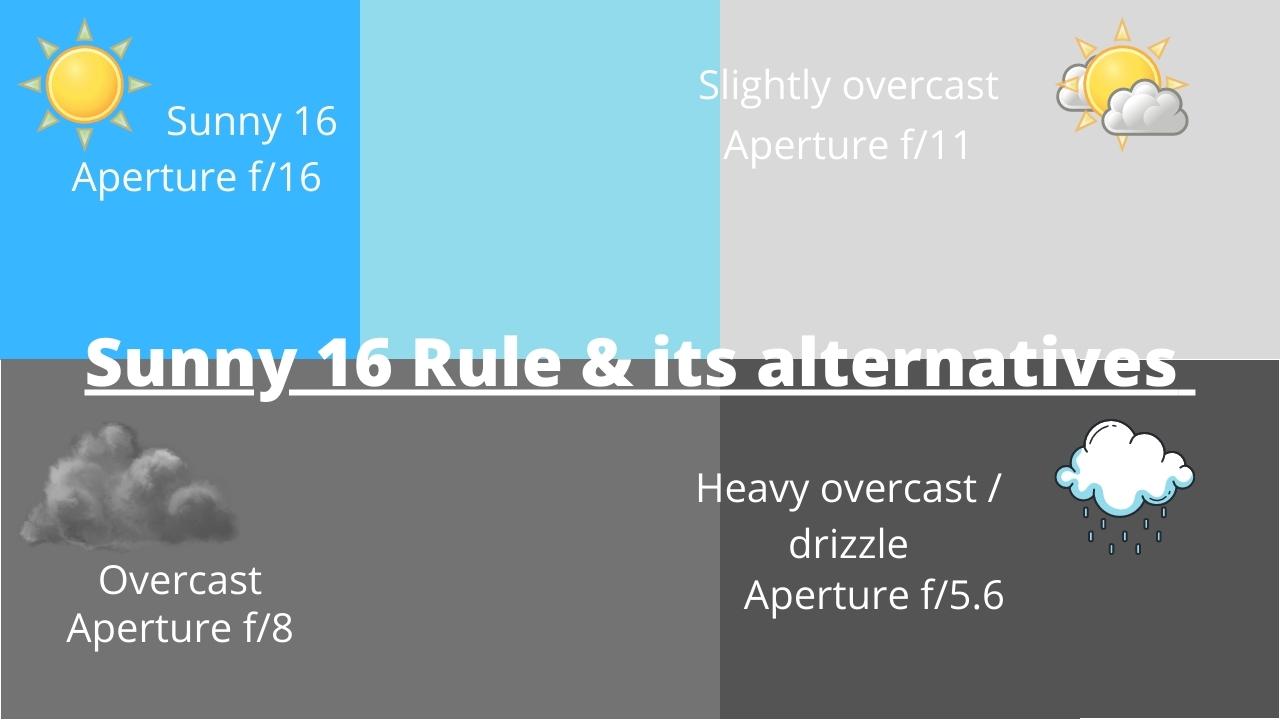

Shooting in Overcast and Other Conditions

But what about conditions when it’s not bright and sunny? Can you use the Sunny 16 rule in other lighting conditions? Yes, you can, albeit by modifying it a little.

Let’s now see how we can take that base camera setting and use it to fit other conditions.

Let’s say that it’s overcast, and you need to open up your aperture to compensate for the lack of light.

Open up the aperture by one stop and choose f/11 as the new aperture. Set ISO to 100 and the shutter speed to 1/100 sec. On the other hand, if it’s a bit more overcast, open up the lens by two stops and choose f/8. Then match it up with ISO 100 and shutter speed 1/100.

For an overcast scene, say even a drizzle, open up another stop and choose f/5.6. Choose the corresponding aperture and shutter speed.

Again, it all depends on the ISO. At ISO 100, the shutter speed should be 100 sec. In the same way, if you’re using ISO 200 or higher, choose the corresponding inverse of the ISO value as your shutter speed.

Effectiveness of the Sunny 16 Rule in Modern Photography

With all digital cameras having excellent built-in metering systems, many of you would think whether the Sunny 16 Rule is at all necessary. It’s pertinent to mention here that the built-in metering system of modern digital cameras works on the reflected light concept.

Let’s elaborate.

The camera’s built-in meter looks at the scene and meters based on the light reflected off of the scene. The built-in meter is fooled to think the exposure is washed out if the scene is too bright, like a snowy landscape. It would compensate by pulling down the exposure.

The opposite happens when the scene has too many dark tones. E.g., a scene with a man wearing a tuxedo. The camera will try to push the exposure thinking that the scene is too dark.

The camera’s metering system is designed in a way to adjust everything down to 18% gray or middle-gray exposure.

This is an inherently incorrect metering process. This is why a lot of professional photographers use the hand-held light meter.

The Sunny 16 rule isn’t based on the same principles the camera’s built-in metering system works. Instead, it works on the principle of incident light—the same as hand-held metering systems.

This is why it’s useful even in the modern era with built-in metering systems.

Beyond the Sunny 16 Rule: Manual Adjustment of Incorrect Exposures

There may be situations where even after applying the Sunny 16 Rule, your exposures may not turn out to be correct. Washed-out highlights are difficult to recover.

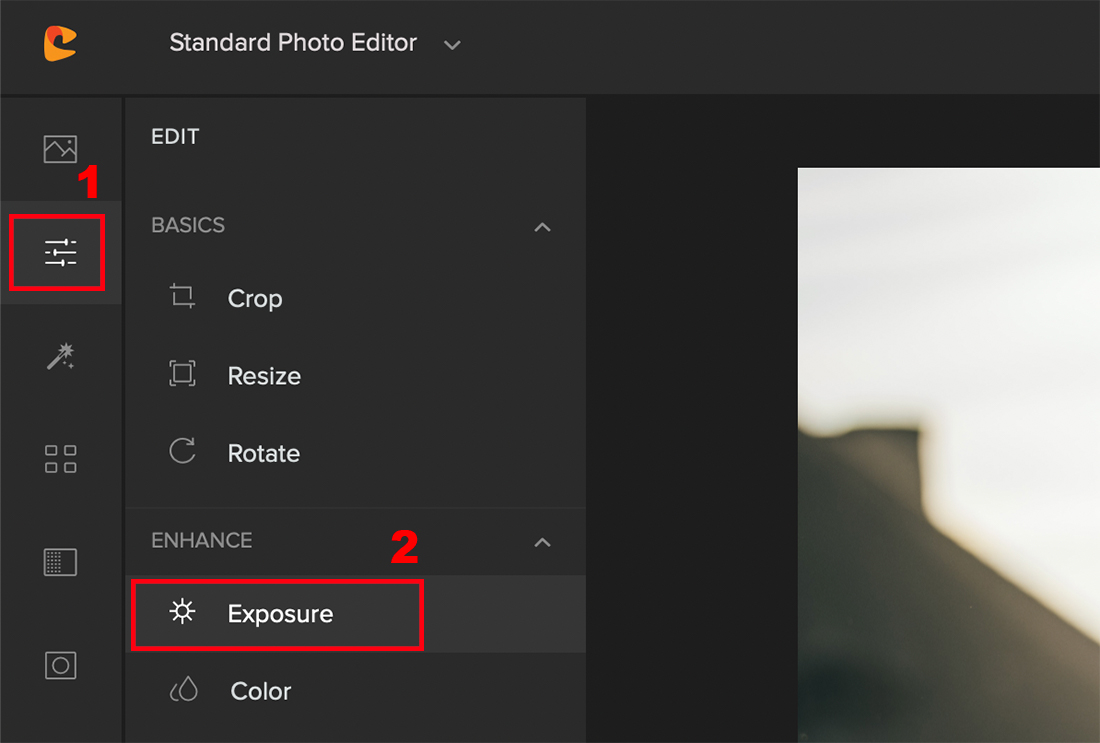

However, if the exposure is slightly darker, it’s easy to recover details using photo editing software like Colorcinch.

Here are the steps:

Step 1: Navigate to Colorcinch.

Step 2: Upload your image using the Upload button.

Step 3: Click on the Exposure button.

Step 4: Adjust the exposure sliders as per your need.

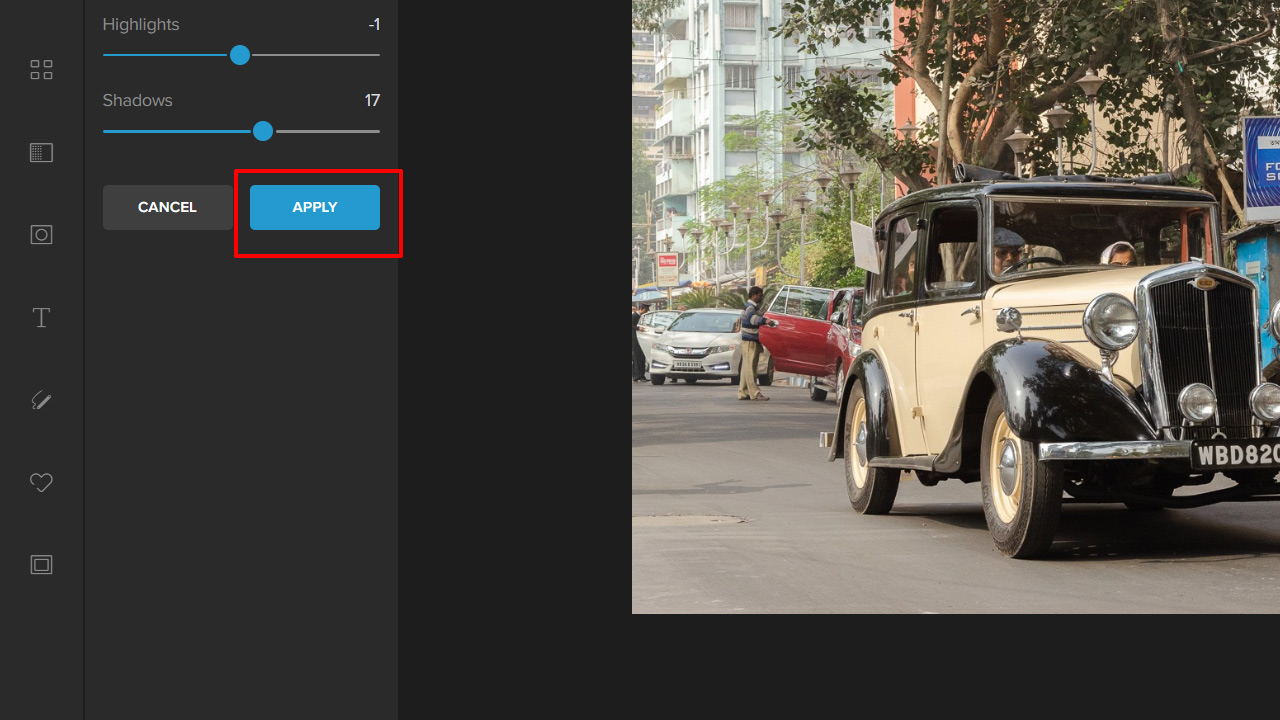

Step 5: Don’t forget to hit the Apply button when you’ve done all the edits; otherwise, you will lose the changes you made.

Concluding Thoughts

The Sunny 16 rule, as you have seen above, is very effective in giving you reasonably accurate metering of a scene when it’s sunny and bright. You don’t even have to use an external light meter or depend on what the camera’s built-in light meter says.

The best thing is that it has multiple uses. You can use that exposure value and then recalculate the correct exposure value given the actual lighting conditions.

Additionally, suppose you wish to play around with depth of field. In that case, you can use the Sunny 16 rule as the starting point and then use the inverse relationship between shutter speed and aperture to recalculate the correct exposure for a given aperture.